“Is the Reformation over?” Prompted by a growing thaw in relations between evangelicals and Catholics in the United States, in particular, Mark Noll and Carolyn Nystrom weighed the evidence and concluded that the answer was (at least in 2005), “No.” Though certain evangelicals and certain Catholics had started to cooperate in matters of social concern, though we had rediscovered how much we share in our Western theological heritage, the division between Rome and Wittenburg, Rome and Geneva, Rome and Wheaton persists.

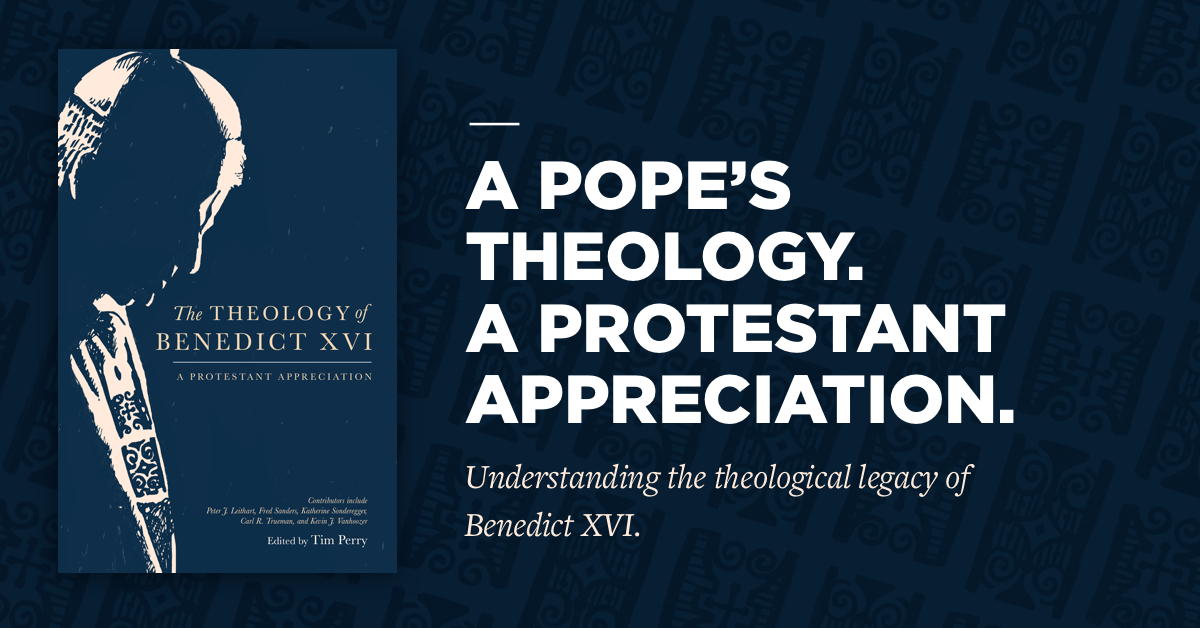

Much has happened over the last fifteen years, but I think that Noll and Nystrom’s answer abides today. Given that conviction, some people might ask why I edited The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation (Lexham, 2019). I hope to sketch an answer here and hopefully convince you, too, that this is a book worth reading—because Benedict is a pope worth pondering.

In the late modern West, times have changed. The social revolution that began in the 1920s was forestalled by World War II and its aftermath, but it picked up steam in the 60s and is reaching full expression now. Well documented by many scholars—especially Charles Taylor in his classic, A Secular Age—it offers a new view of humanity. Human nature is constructed by desire, and the will and wealth to actualize that desire is ascendant. Indeed, there is no such thing as universal human nature; there are only natures as individuals construct their own, insofar as they are able. This anthropology often goes begging in debates about sexuality, the environment, beginning and end of life, and even transhumanism and quantum computing. Examples multiply.

In this brave new world, justification by faith alone simply is no longer the article by which the Church stands or falls—and not because the Lutheran World Federation and the Roman Catholic Church issued a joint declaration about justification in 1999. In the wider cultural sphere, the nature of salvation is not an issue. It has been supplanted by questions like, “What does it actually mean to be human?” “Is there such a thing as a common humanity?” “Where are the limits (if any) in augmenting or altering our biology?” Even, “Who counts as a human being?” In these questions, traditional-minded Protestants and Catholics are (or ought to be) in lockstep bearing consistent, if currently unpopular, witness to the world.

In this witnessing, we have no better example than Benedict XVI. How so? In three ways:

(1) Benedict believes in reason. Across the political spectrum throughout the West, words are no longer used to discover, articulate, and defend the truth. Instead, our political class has become a culture of leaders like Pilate, cynically asking whether there even is such a thing. Today, words are used as the means to actualize desire. Thus, if science helps me, I deploy science to actualize my desire (“I was born this way and must act accordingly”). If science stands in my way, I cast it aside (“I feel different than how I was born and must alter my biology accordingly”). Words are used to bring feelings from the immaterial world of the subjective into material objective reality. Truth quite literally be damned if it gets in the way.

Against this, Benedict doubles down on the unique “fittedness” between human reason and creation. Creation is structured rationally; our reason is structured rationally so as to know it. This commitment to reason furthermore reflects a view of human dignity in which we are not simply desires seeking actualization. Rather, we can distinguish between noble and base, and we can learn both to attend to those desires that better us and to discipline those that do not. Christians of all stripes, it seems to me, ought to be similarly committed.

(2) Benedict believes in revelation. Not only does Benedict believe that human beings have been endowed by their creator to know the world he created, but also that he has in fact spoken to us. Through the creation, the election of Israel, and especially in the incarnation, God invites human beings know and enjoy him. Many Western Christians have opted for a universalism that blithely holds all creeds to be indifferent regarding the truth, all “saving” (at least in terms of providing spiritual satisfaction).

Benedict, however, insists—again unpopularly—that God has disclosed himself uniquely; that we can discover not only truths about God, but God himself. Those ways that lead away from Jesus, however spiritually rich they may be, however God may graciously work in and through them, do not provide paths to God. Jesus alone is the way, the truth, and the life.

(3) Benedict believes in a common human nature. Of a piece with his commitments to reason and revelation is a commitment to a shared definition of being human across time, space, culture, gender, or any other divider. What makes me a human being is what makes you a human being. Human nature is not constructed by individuals with wills strong enough and wealth ample enough. Rather, it is something all human beings share, something created by God, something—however marred by sin—that is good and worthy of redemption. Such that the Son of God considered equality with God not something to be grasped but made himself nothing. He took up all that it means to be human in order to save all who believe.

That’s where this debate over human nature finally ends up: salvation. If there is no stable human nature, if human natures (plural) are only conflicting collections of desires awaiting realization by individuals, then there is nothing for the Son of God to take up. There is no incarnation, and we are not saved. We’re left grasping after some sort of neo-gnostic self-salvation that only the superhuman and the super wealthy will be able to achieve. The rest of us are dead in our sins and are above all people to be pitied.

Reason—what can I know? Revelation—can I know God? Being human—who am I? These are questions that define our time. They provoke no substantive disagreement between Protestants and Catholics. In working at answering them, God has blessed his church with a teacher: Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI. Our collection is an attempt to discern the gifts God has given through this teacher and to thank God and Pope Benedict for the teaching.

This guest post was written by Tim Perry, editor of The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation (Lexham Press, 2019).