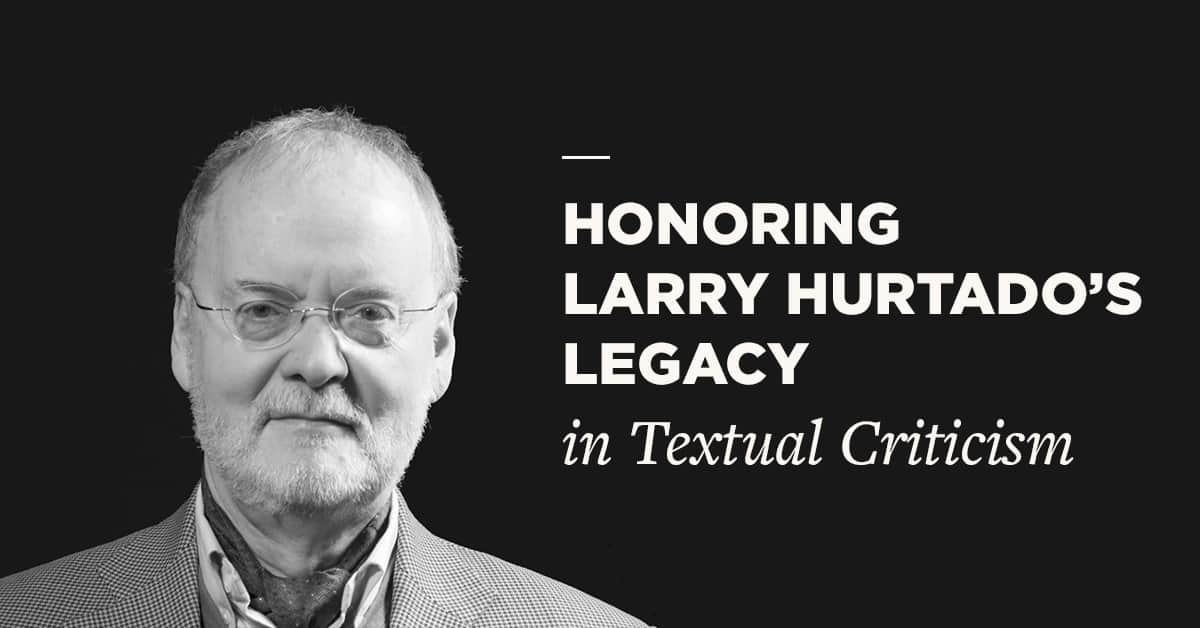

This week, in remembrance of his death nearly one year ago, Lexham Press will be running a series of blog posts honoring Larry Hurtado’s legacy and contributions to biblical scholarship. The first post was focused on Christology. The second post covered Hurtado’s contributions to Markan Studies. This third post was written by Tommy Wasserman.

Many years ago, when Larry Hurtado had been invited to my alma mater, Lund University, to speak on early Christian worship, I mentioned to some of my colleagues that I knew Larry Hurtado from my field, New Testament textual criticism. “What?” they replied. “Is he working in textual criticism? We didn’t know that.”

Hurtado’s many publications in New Testament textual criticism are probably not as widely known as those in other fields like Christology and Markan studies. The reason for this is not a difference in quality, but probably one in popularity, although the field is currently growing fast, so this may be changing.

The situation was worse in the 1970s when Hurtado submitted his dissertation “Codex Washingtonianus in the Gospel of Mark: Its Textual Relationships and Scribal Characteristics” to Case Western Reserve University in 1973 (later published by Eerdmans in 1981), as reflected in the first sentences of the preface:

In the early stages of my theological training I felt that Textual Criticism was a very arid and uninviting pastime. The present contribution reflects, however, a more positive appreciation for the discipline.[1]

I assume that Hurtado’s Doktorvater, Eldon Epp, played an important role in this growing appreciation. A few years earlier Epp had held a lecture on what he regarded as “The Twentieth Century Interlude in New Testament Textual Criticism.” In the published version, Epp suggested there had been an interlude ever since the golden era of the nineteenth century, which had peaked with the work of Westcott and Hort.[2] One of his examples of the interlude was “the Caesarean text affair.”[3] Ever since the Caesarean text had been identified by Kirsopp Lake and Robert P. Blake in 1923, there were suspicions about the integrity of this text-type.

The ensuing debate was significant for New Testament textual criticism. If Papyrus 45 and Codex W were early Caesarean witnesses in Mark, as had been suggested by some scholars, then the Caesarean text would be a very early and important text-type. Epp’s doctoral student, Larry Hurtado took on the challenge. He convincingly called into question the validity of the so-called “pre-Caesarean text.”[4] The early witnesses Papyrus 45 and Codex W showed no particular affinity with later witnesses thought to represent the Caesarean text-type, at least not in Mark where most of the work on the Caesarean text had been done. For Epp, Hurtado’s thesis clearly represented one of the few vital signs of the discipline at the time; the interlude was drawing to a close.

Two decades later it was Hurtado’s turn to describe the field of New Testament textual criticism in an essay titled “Beyond the Interlude? Developments and Directions in New Testament Textual Criticism,” and, as the title implies, he took the earlier pessimistic surveys by his Doktorvater as the points of departure.[5]

Hurtado stated at the outset that Epp’s analysis of the situation was essentially correct, but now he could cite various signs of vigor in the discipline and conclude that things were not as bad. In his description, he specifically singled out five areas where development had taken place and proposed that these areas indicated the directions the discipline should be going in the future. These areas were:

- thorough examination of important witnesses;

- better knowledge of scribal habits;

- a more clear understanding of the transmission of the New Testament in the “crucial second century;”

- connecting textual criticism to a wider historical investigation of the early church; and

- the use of computer technology in various ways (for example, when collating MSS).

In my opinion, Hurtado, through his scholarship and activity has contributed not only to the general interest in the field, but to all five of these specific areas; he surely practiced what he preached. At the same time, however, there was a certain focus in his scholarship on the early text of the New Testament, corresponding to his interest in the earliest Christian artifacts, to the devotion of Jesus in earliest Christianity, and to the (presumably) earliest canonical Gospel.

Because space is limited, I have singled out two specific contributions on early Christian artifacts and textual criticism, respectively, because they are largely representative of Hurtado’s scholarship in these areas. Incidentally, both appeared in 2006. I will start with the monograph, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Eerdmans), where Hurtado focuses on the early Christian manuscripts not merely as sources of texts but as artifacts in their own right, significant for the study of Christian origins and the emergence of a Christian book culture.[6]

In the first chapter, Hurtado describes various Christian manuscripts from the second and third centuries that contain “Old Testament,” “New Testament,” and “apocryphal” texts, being aware that these convenient labels are potentially anachronistic. In some cases, it may be difficult to decide whether a Greek Old Testament manuscript is Jewish or Christian, but Hurtado does not let the few ambiguous cases overshadow the unambiguous. Significantly, for the emergence of a New Testament canon, Hurtado notes that some manuscripts occasionally contain several writings—for example, P45 (four Gospels and Acts) and P75 (Luke and John)—but these are always biblical texts. No noncanonical texts are collected in the same way.

In chapter two, Hurtado demonstrates with data from the Leuven Database of Ancient Books (LDAB; https://www.trismegistos.org/ldab/) how the early Christian scribes preferred the codex over the bookroll, in contrast to the contemporary book culture. The preference was intentional to distinguish the writings they treated as scripture. Conversely, Hurtado argues that a fragment like P. Oxy. 655, with the Gospel of Thomas written on a roll, was not prepared for use as scripture.

Chapter three considers the nature and use of the nomina sacra in early manuscripts. Hurtado outlines the various forms, including the earliest four abbreviations of the divine names—θεός, Ἰησοῦς, κύριος and χριστός—suggesting that the phenomenon is a Christian innovation (there are no nomina sacra in unambiguous Greek Jewish manuscripts of the first century) but possibly influenced by the Jewish interest in gematria. The convention, he suggests, may have begun with writing Jesus’ name in the two-letter suspended form IH, which also held a numerical significance that connected it, by way of gematria, to the Hebrew word for “life.”

Chapter four is concerned with the staurogram (formed by combining the Greek letters tau and rho) and its significance for Christian origins. Hurtado argues that the staurogram is the earliest visual representation of Jesus on the cross predating the Constantinian period. The final chapter treats briefly various other phenomena in the early Christian manuscripts (sizes of codices and margins, columns, various reader aids, corrections, etc.), providing more information about the scribes and communities who produced and used them. For example, reader aids like textual division provide insights into early Christian interpretation.

The earliest Christian manuscripts on papyri have most often been studied with a focus on their texts. In this monograph, Hurtado convincingly demonstrates how these manuscripts—the earliest Christian artifacts—can provide valuable insights into Christian origins.

The second publication I would like to consider is “The New Testament in the Second Century: Text, Collections and Canon” (2006), because it sums up much of Hurtado’s scholarship in the field of textual criticism.[7] In this essay, a text critic with long experience in the field and with the required “knowledge of the documents” (to use Hort’s words) offers his general view of the crucial second-century text of the New Testament, which is a highly debated issue. The article treats three significant areas, or “processes,” in the period of the second century.

The first area is the textual transmission of the NT writings. Hurtado reviews the early manuscripts, including the newly published Oxyrhynchus material. He concludes that the fragments from the second century justify the view that the more substantial manuscripts from the third and fourth centuries do not reflect some major recension of the text toward the second century. On the contrary, they reflect various points along a spectrum from more controlled texts reflecting a concern for careful copying to comparatively more free and careless copying. The former controlled texts are thus reliable witnesses of the text of the writings they contain.

Also belonging to the area of textual transmission are the second-century citations by Christian writers. Scholars like Helmut Koester and William Petersen have argued that the loose and fluid wording of the patristic citations means that the text itself was considerably more fluid than is reflected in extant MSS. Here, however, Hurtado appeals to Barbara Aland’s objection that their analysis disregarded the wider literary practices of the time. Especially in the first half of the second century there was apparently a lack of “text-consciousness” (Textbewusstsein).

The next “second-century” area is the issue of collections. Here Hurtado notes that several recent studies agree in pushing back the likely origin of a fourfold Gospel collection to the earliest years of the second century. He reviews David Trobisch’s thesis of a “canonical edition” of the complete NT as we now know it in existence as early as the mid-second century, which, according to Hurtado, is probably too early.[8]

He further notes that the very fact that the NT writings were brought together in collections had an effect on the transmission of the text. For example, the long ending of Mark probably presupposes a fourfold Gospel collection, and so do the many harmonizations of one Gospel to another. Earlier in the essay Hurtado points out that the regular liturgical reading of the four canonical Gospels also helps to account for the abundance of harmonizing variants. In this connection, I appreciate his remark that liturgical usage would at the same time also have set real limits on how much a writing could be changed without people noticing (and objecting). The repeated liturgical reading is yet another factor speaking against a wild and uncontrolled second-century text.

Hurtado also mentions how an early Pauline letter collection may have affected the textual transmission. A collection could have led to recomposition and revision of the letters. Thus, Harry Gamble has argued that there was an abbreviated version of Romans with fifteen or even fourteen chapters intended for wider ecclesiastical circulation in a letter collection.[9] Gamble refers to the omission of the letter’s destination in some MSS, and to the textual instability of the concluding doxology of Romans, which appears in chapter 14, 15, or 16 in the MSS.

The third and final second-century area is the emergence of a New Testament canon, which is of course closely related to the other areas. In fact, those writings that made it into the New Testament during the canonical decision-making at later stages were those writings that had been widely spread, collected, and accepted for liturgical reading. Several of the earliest papyri were most likely produced for public reading. There are even reader aids in the earliest extant papyrus fragment P52.

Hurtado suggests that the cumulative evidence bears witness to an emergent Christian “material culture” and a distinctive Christian literary ethos. In this regard, he thinks we may even speak of a “text-consciousness,” influential in the early Christian era, in spite of the fact that Christian writers felt free to appropriate the contents of texts. He points to several examples from the New Testament itself (Rom 15:17–21; 2 Cor 10:9–11; 2 Tim 4:13; Rev 21:18–19) and concludes:

We have, perhaps, somewhat romantically regarded the earliest Christian circles as so given to oral tradition that their writings took a distant second place in their values. From the earliest observable years Christianity was a profoundly textual movement.[10]

When I consider these and Larry Hurtado’s numerous other contributions to the field of textual criticism and Christian artifacts over a period of nearly half a century, I can tick off all five areas he outlined in his essay on directions and developments in textual criticism beyond the interlude. He has provided us thorough examinations of early witnesses to the text of the New Testament, better knowledge of the scribal habits of these witnesses, and a clearer understanding of the transmission of the New Testament in the crucial second century. Last but not least, he has connected manuscript studies and textual criticism to a wider historical investigation of the early church in areas such as liturgy, canonization, emergent Christian “material culture,” making good use of the best available digital tools, in particular in his research on the manuscripts as early Christian artifacts.

Personally, I am deeply indebted to Larry as a fine scholar, dear friend, and role model. I miss him.

In honor of Larry Hurtado’s work, we’re offering Honoring the Son: Jesus in Earliest Christian Devotional Practice for just $5 through the end of the month.

[1] Larry W. Hurtado, “Codex Washingtonianus in the Gospel of Mark: Its Textual Relationships and Scribal Characteristics” (Ph.D. diss., Case Western Reserve University, 1973), v.

[2] Eldon J. Epp, “The Twentieth-Century Interlude in New Testament Textual Criticism,” JBL 93, no. 3 (1974): 386–414.

[3] Epp, “Interlude,” 393–96.

[4] Hurtado’s thesis was subsequently published as Text-Critical Methodology and the Pre-Caesarean Text: Codex W in the Gospel of Mark, SD 43 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981).

[5] Larry W. Hurtado, “Beyond the Interlude? Developments and Directions in New Testament Textual Criticism,” in Studies in the Early Text of the Gospels and Acts, ed. D. G. K. Taylor (Birmingham: University of Birmingham Press, 1999), 26-48. This book also appears as volume 1 in the Text-Critical Studies series (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1999).

[6] Larry W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006).

[7] Larry W. Hurtado, “The New Testament in the Second Century: Text, Collections and Canon” in Transmission and Reception: New Testament Text-Critical and Exegetical Studies, ed Jeff W. Childers and D. C. Parker, Texts and Studies; Third Series 4 (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006), 3–27.

[8] David Trobisch, The First Edition of the New Testament (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[9] Harry Gamble, The Textual History of the Letter to the Romans: A Study in Textual and Literary Criticism, SD 42 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1977).

[10] Hurtado, “The New Testament in the Second Century,” 25–26.

Dr. W.,

a great article on a truly extraordinary man. Your obvious admiration and affection for Dr. H. reminds me of the way he often wrote of those who came before him.

Though only knowing him through his books, numerous articles and most of all through his blog, which included substantial interactions on many issues; your article also warms my heart and reminds me that his untimely death was a great loss across a wide range of Christian scholarship.

Tim