In a few short decades in the latter half of the twentieth century, the interpretation of the Bible underwent a notable shift such as has happened only occasionally over the last few thousand years. During this time the focus in biblical interpretation began to shift from what the text can teach us about the past to also include what the text can teach us about the text (and ourselves). Increasingly, the Bible began to be viewed and read not just as a religious or historical document but also as a literary text.

This shift in biblical interpretation correlates strongly with the sea change that took place in the Western world during the twentieth century. Two world wars, the end of colonialism, and a sexual revolution formed the backdrop for the ?narrative turn? in the study of world literature. There were many more factors than we can possibly mention here. Yet, few have anything to do with the Bible itself. By acknowledging this up front, we can gain a positive perspective on the literary approach to the Bible. It is just one philosophical approach. If we can recognize that the various historical and literary approaches, with their respective methods, are simply tools in an interpreter?s toolbox, we can faithfully use those tools without fear or blame.

The confusion over these literary foundations has led to the rise of a number of inaccurate assumptions about the literary approach to the Bible. Here we mention the most frequent objections to the literary approach to the Bible:

- The Bible is not literature. The problem with this statement is what one means by ?literature.??Usually this statement implies that literature is a specific group of fictional works that range from Milton to Hemingway. However, the term ?literature,? while traditionally used to mean ?to designate fictional and imaginative writings?poetry, prose fiction, and drama,? now means ?any other writings (including philosophy, history, and even scientific works addressed to a general audience) that are especially distinguished in form, expression, and emotional power.??The former definition is closer to what literary critics mean when they use the term ?(literary) canon.? As we rely on current definitions of the word ?literature,? the Bible is literature.

- The literary approach is new and therefore anachronistic. The first known occurrence of literary criticism in the West dates back to the production of Aristophanes? Frogs in 405 bc.?After this, Aristotle (384?322 bc), Longinus (fl. late first century ad), and Dionysius of Halicarnassus (fl. late first century bc) produced works on literary theory and criticism that are still extant today, not to mention that the Teacher in the book of Ecclesiastes mentions at least one aspect of literary criticism (Eccl 12:9?10). While some of the individual methods within the broad umbrella of the literary approach to the Bible are new and could be used anachronistically, the approach itself is not new and actually predates the nt (and some parts of the ot as well). Further, some methods within other approaches (such as the historical-critical approach, the most notable predecessor to the literary approach) are also new and can also be used anachronistically. Therefore, anachronism is always a concern for interpreters of ancient texts, regardless of approach and method.

- The literary approach has no final ?answer? in interpretation or endpoint?many different interpretations are equally valid. This claim is partly true and partly false, but it only has a little to do with the literary approach itself. ?Differences in interpretation have existed from the moment of creation of any biblical text. In past generations, it was not the method that provided an end to interpretive discussion but rather an authority (such as a council, a church, a church leader, or a consensus). It is true that one of the results of recent literary theory is a proliferation of different methods (and as a result, interpretations), but this is more a result of the proliferation of ideologies in the Western world in the last century than it is of any movement or expectation in the field of biblical studies.

- The literary approach is not scientific or rigorous (as the historical approach is). This argument depends a great deal on who the interpreter is and whether an appropriate tool is selected. Every approach to Scripture will have less rigorous examples and more rigorous examples, regardless of the approach. Further, ?scientific? and ?rigorous? are modern ideals that earlier interpreters of Scripture may not have held to be extremely important (as they were not influenced by the modern worldview).

- The literary approach is not historical/avoids historical concerns. This last objection is the most frequently noted by those critical of the literary approach. It is true that many literary approaches to Scripture avoid or ignore historical questions and concerns. But it is not true in all cases. Furthermore, applications of the literary approach to the Bible are often ahistorical, but rarely anti-historical.?In other words, when an interpreter takes a tool from a literary method out of their toolbox, they are letting the reader know that they are focusing on literary concerns more than historical concerns. The same is true when an interpreter decides to employ the historical approach?that interpreter typically is not trying to avoid literary questions; rather, it is just not their focus in this situation. Currently, biblical scholars are using the literary approach to focus on the text, but increasingly they are not shunning historical concerns and questions when appropriate for their interpretive goals.

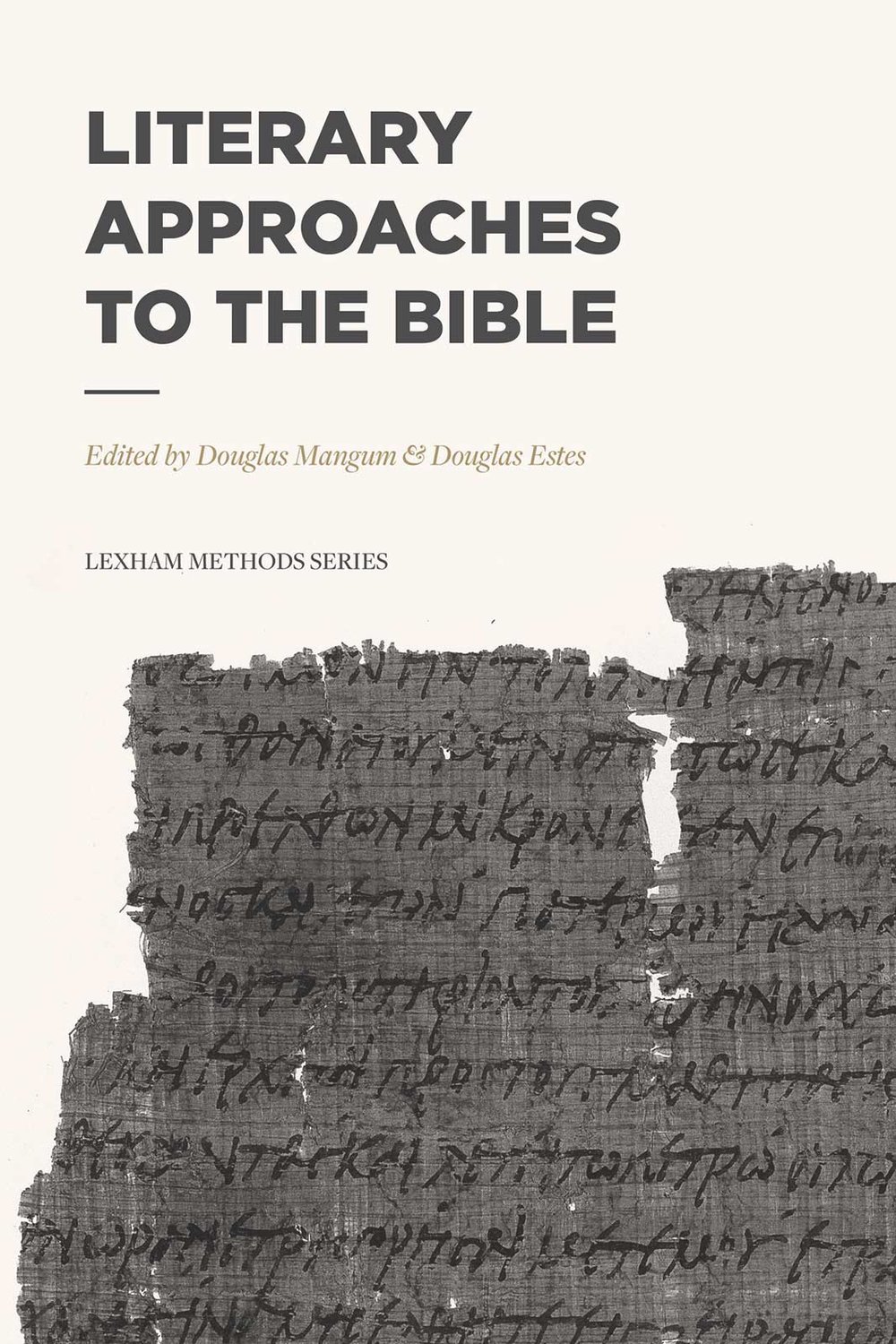

The detailed analysis of biblical books and passages as written texts has benefited from the study of literature in classical philology, ancient rhetoric, and modern literary criticism. Literary?Approaches to the Bible?introduces the various ways the study of literature has been used in biblical studies.

Deepen your biblical education with the Lexham Methods Series. All four volumes are available now.