Today, this question raises theological temperatures to a boil. Three hundred years ago, at the dawn of the evangelical movement, ministers banned this question from being asked from their pulpits. The early evangelicals took their questions, and more importantly, their answers, elsewhere.

Trumpeting across the field, a voice could be heard from a person too far away to be seen. Amid the horses, commotion, and shuffling of feet, a voice roared: “But that there is really such a thing, and that each of us must be spiritually born again, I shall endeavour to shew.” The voice was that of George Whitefield (1714‐1770).

Whitefield preached this sermon, reading it word for word, at the Parish Church of St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol, England in 1737 at the tender age of twenty‐two. But, two years later, things had changed. For one thing, he would need to raise his voice quite a bit for everyone to hear him. And raise it he did.

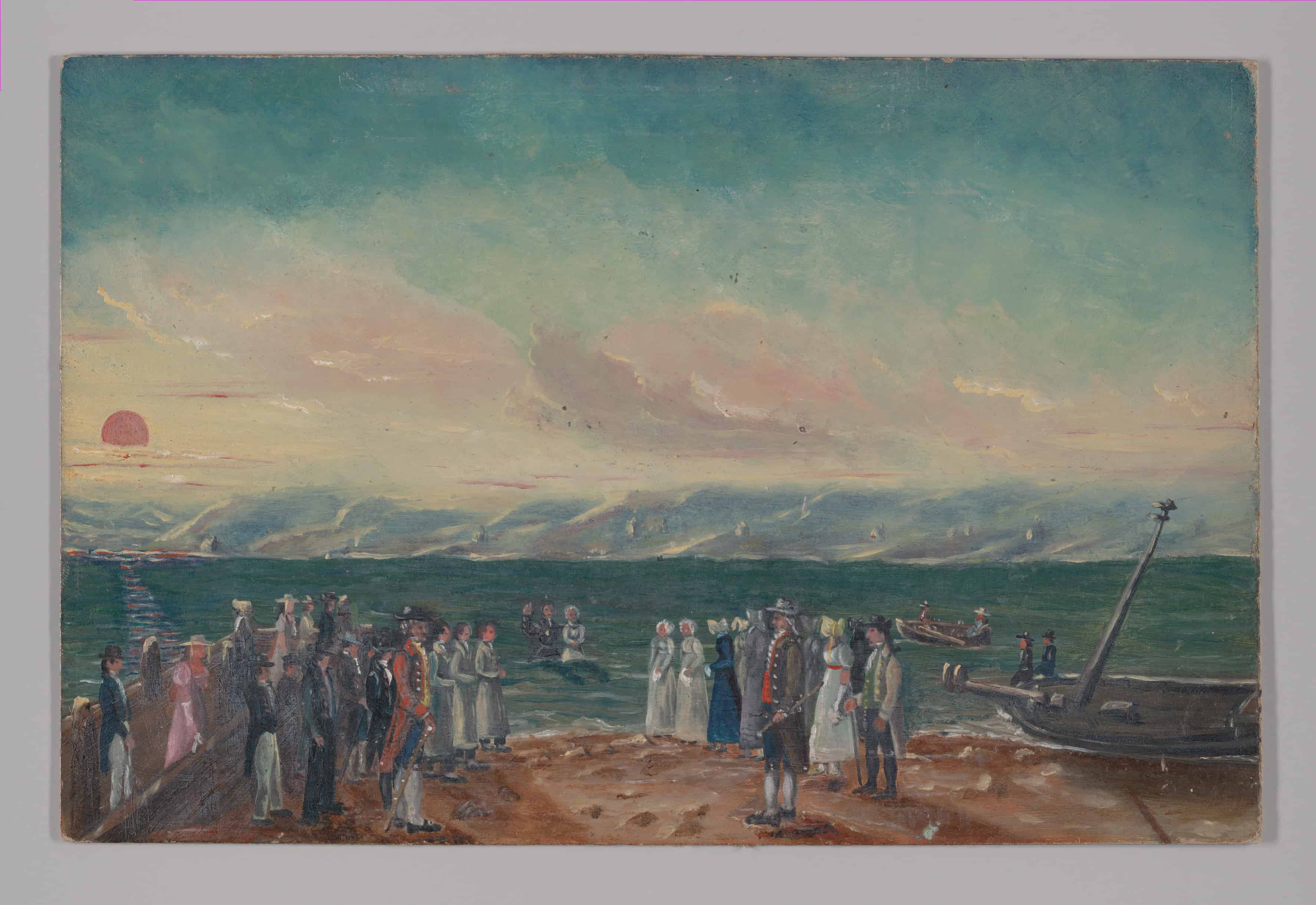

Whitefield was denied the right to preach at St Mary Redcliffe and many other churches far and wide, due to his contested insistence upon the necessity of the new birth. On February 17, 1739 Whitefield ascended a small hill and preached outdoors to two hundred rough and rugged coal miners in the colliers of Kingswood. Six weeks later, Whitefield introduced his friend, mentor, and sometimes adversary, John Wesley (1703‐1791) to open‐air preaching.

It might be difficult for modern Christians to understand why Whitefield and Wesley, both being ordained ministers, were denied access to pulpits. They resorted to preaching outdoors because they believed that every person needed to be born again.

Church-goers in Wesley and Whitefield’s day, whether pious or lax, felt little need to be born again. Critics argued that Wesley and Whitefield’s insistence upon a faith‐based conversion experience for someone who was baptized as an infant was not conversion or being born again at all, it was simply an act of repentance for those already born again. Wesley and Whitefield were dismissed as “young quacks in divinity” vending their “pills and potions” doing “much injury to some well‐meaning patients.”

Wesley and Whitefield were not deterred. Early evangelicalism and the Great Awakening revivals of the 18th century are built upon the beliefs of these “young quacks in divinity.”

In the ensuing decades, Wesley and Whitefield preached and worked out a theology of conversion that I explain as inaugurated teleology. They understood conversion to be an inauguration: a definite, punctiliar, beginning that comes through the new birth and regeneration via faith. They also understood conversion to be teleological: the reforming of the image of God within a person towards the purpose and end for which they were created.

Wesley and Whitefield are well‐known for their cantankerous disagreements during the ‘Free Grace Controversy’ (1739‐1744) regarding Whitefield’s Calvinism and Wesley’s Arminianism. I argue in Born Again, however, that they were in significant agreement regarding the doctrine of conversion. I explain how Wesley and Whitefield understood conversion theologically in light of their views on baptism, assurance of salvation, and recognition, or lack of, a “conversion testimony.”

The continued modern evangelical insistence to be ‘born again’ is evidence of Wesley and Whitefield’s foundational theology of conversion. My hope is that evangelicals, non‐evangelicals, historians, theologians, pastors, and evangelists will not only deepen their understanding of evangelical conversion and of gain a snapshot of early evangelicalism (perhaps as a point of reference to compare with modern evangelicalism), but, echoing Whitefield, that my book Born Again will also help people ponder that “there is really such a thing, and that each of us must be spiritually born again.”

This guest post was written by Sean McGever, author of Born Again: The Evangelical Theology of Conversion in John Wesley and George Whitefield (Lexham Press, 2020).