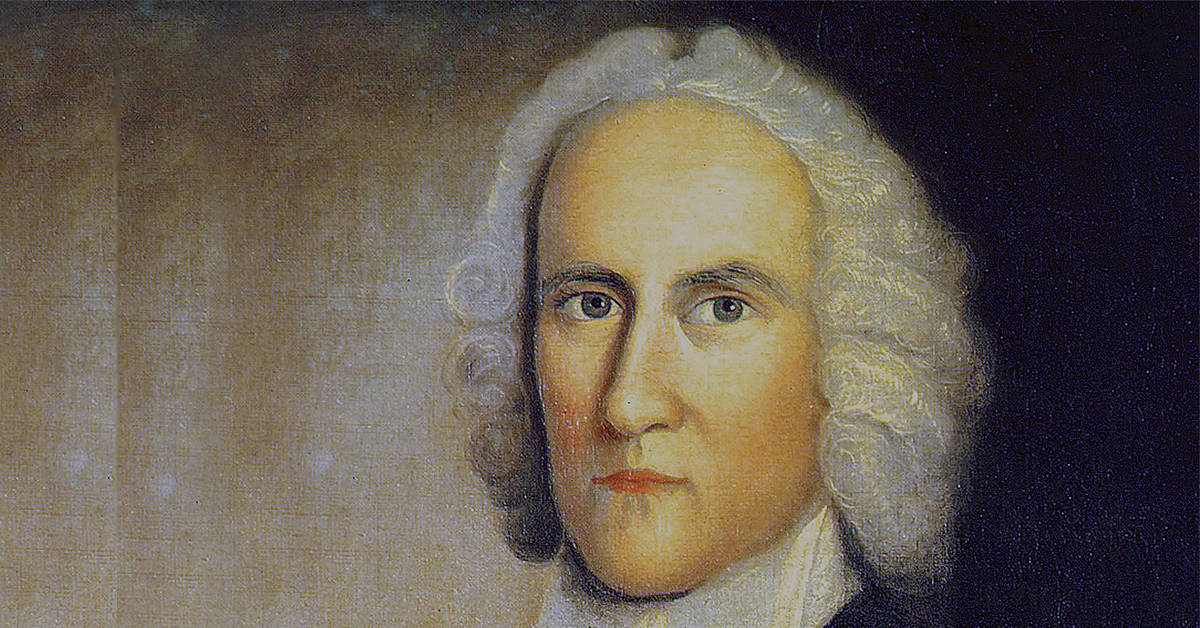

In this excerpt from The Federal Theology of Jonathan Edwards, Gilsun Ryu provides an overview of the origins of Jonathan Edwards’s federal theology and it’s roots in biblical exegesis.

Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), one of the most intriguing federal theologians, inherited classical federalism from Reformed orthodoxy. Federal theology is a form of Reformed covenant theology, which emphasizes the representative principle of the headship of the first and second Adams. This theology not only stemmed from earlier writers, such as Irenaeus, Augustine, and the Reformers (Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, Heinrich Bullinger, and others), but also was maintained and developed by Reformed orthodoxy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Since the Westminster Confession of Faith represented the full development of federal theology into a confessional status by clearly distinguishing between the doctrines of the covenants of works and grace, it became a theological commonplace in Reformed orthodoxy.

Edwards neither wrote about his view of federal theology in a systematic way nor published a treatise on his exegetical method. Nevertheless, his federal theology occupies a place of considerable significance in his biblical exegesis. This is clear from the fact that his use of the federal schema—the covenant of redemption, the covenant of works, and the covenant of grace—is interwoven with his biblical writings. Edwards employed the federal schema in his biblical works, including his “Blank Bible,” “Notes on Scripture,” “Miscellanies,” typological writings, and hundreds of sermons from his extant corpus. This implies that one cannot fully understand Edwards’s federal theology without his biblical exegesis.

A significant element in Edwards’s federal theology is its focus on the history of redemption and the harmony of the Old and New Testaments. In formulating his doctrine of the covenant, Edwards took great pains to understand salvation history through biblical exegesis, so that he attempted to harmonize the whole Bible. This can be seen in his comments about his unfinished works A History of the Work of Redemption and The Harmony of the Old and New Testaments. First, the theme of redemptive history was of utmost importance in Edwards’s theological thought. In a letter to the trustees of the College of New Jersey, Edwards writes:

I have had on my mind and heart, (which I long ago began, not with any view to publication,) a great work, which I call a History of the Work of Redemption, a body of divinity in an entire new method, being thrown into the form of a history; considering the affair of Christian Theology, as the whole of it, in each part, stands in reference to the great work of redemption by Jesus Christ.

Edwards’s attention to the history project is also found in three notebooks, which Edwards wrote during the Stockbridge period (1751–1757). Moreover, Edwards’s interest in redemptive history is evident in his 1739 sermon series and the “Miscellanies.” From these four categories of evidence pertaining to Edwards’s view of the history of redemption, the redemptive-historical theme appears to be one of the most important theological lenses through which Edwards viewed the Bible.

Edwards’s view of the history of redemption can be clearly seen in his sermon series of 1739, titled A History of the Work of Redemption. In this work, Edwards’s concept of the work of redemption is focused on the final purpose in God’s design, which was made in the covenant of redemption among the persons of the Trinity. Edwards presents the purpose as follows: (1) “to put God’s enemies under his feet,” (2) “to restore all the ruins of the fall,” (3) “to bring all elect creatures to a union in one body,” (4) “to complete the glory of all the elect by Christ,” and (5) “to accomplish the glory of the Trinity to an exceeding degree.” This purpose is accomplished by the work of redemption as “the principal means.”6 This indicates that God’s design before the creation of the world can be seen through the process of history.

Moreover, the redemptive-historical character of Edwards’s federal theology is related to his own comprehensive understanding of the Bible through his biblical exegesis. Specifically, Edwards’s emphasis upon the history of redemption comes as a necessary aspect of his view of the harmony of the Bible. In the history project, Edwards intended for “every divine doctrine” to “appear … in the brightest light … showing the admirable contexture and harmony of the whole.” The harmony Edwards refers to indicates something successive in all secular historical events and those recorded in the Bible. After describing the history project, Edwards begins to explain “another great work” which he planned to write. In the same letter, Edwards writes, “I have also for my own profit and entertainment, done much towards another great work, which I call The Harmony of the Old and New Testament.” The harmony between the Old and New Testaments has to do with the “exact fulfillment” of the Word of God in all the historical events of the world. Examining Edwards’s harmony project, Nichols suggests that Edwards’s concept of “redemption history and a covenantal system” is a framework for harmonizing the Old and New Testaments. Thus, it appears that not only is the redemptive-historical lens crucial to Edwards’s approach to the Bible, but the theme of the history of redemption and the covenant system is also a framework for harmonizing the whole Bible.

Edwards understood the relationship between the history of redemption and the covenant system to be focused on the biblical teaching on salvation from sin. Edwards developed his federal theology from his comprehensive understanding of the Bible in attempting the harmony between the Old and New Testaments. In doing so, Edwards examined a large body of biblical texts, not only considering etymological, cultural, theological, and practical aspects but also employing various methods, like literal, linguistic, contextual, typological, and allegorical interpretations.

While Edwards finds his covenant scheme in various texts from which he extrapolates the relationship of the first Adam and the second Adam (Christ), original righteousness and original sin, total depravity, imputation of sin, and so forth, one of the standard examples of the covenant schema can be seen in his sermon on Genesis 3:11, in which Edwards explains the relationship between Adam and his posterity. Genesis 3:11 is related not only to the Gospel of John and 1 John 3:8, which reveals the consequence of Adam’s sin, but also to Hebrews 2:14. Moreover, Edwards connects these verses to Romans 5:14, 1 Corinthians 15:45, and Hebrews, where the terms “the first Adam” and “the second Adam” come from. By perceiving the covenantal framework in his exegetical perspective, Edwards attempted to interpret the redemptive–historical nature of salvation within his wider framework of the doctrinal unity between the Old and the New Testaments. Thus, one of the most important frameworks for interpreting the history of redemption is the doctrinal harmony of the Bible through federal theology.

This post is adapted from The Federal Theology of Jonathan Edwards: An Exegetical Perspective by Gilsun Ryu (Lexham Press, 2021).