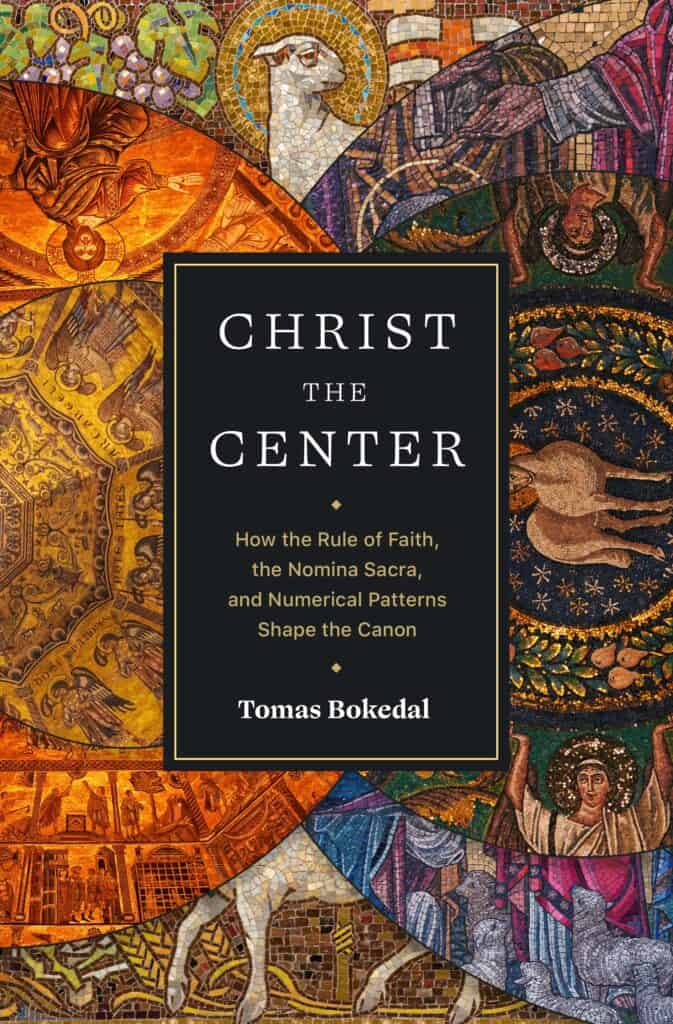

In Christ the Center:Christ the Center: How the Rule of Faith, the Nomina Sacra, and Numerical Patterns Shape the Canon, Tomas Bokedal shows how the canon is shaped by numerical patterns of nomina sacra—scribal reverence for divine names. During our interview with Bokedal below, we explore how the process of being a Christian and reading Scripture are intricately connected to nomina sacra.

Lexham Press: Why do you write?

Tomas Bokedal: My basic task is to search for knowledge and to share my findings with others. My research focus is twofold: on the one hand, the historical origins of Christianity with particular focus on Scripture and theology and how they relate to one another, and, on the other, what it means to be and become a Christian. These research projects both deal with questions of Christian identity, which in my view are important to all of us. To me it is natural to share my writing with a broad readership.

LP: Share things about yourself that only your friends would know.

Bokedal: During my high school years in rural Sweden, I was the only boy among a large number of girls in an elective class on typing. I did not then know how much of my future career I would spend typing.

LP: What is the big picture idea of Christ the Center?

Bokedal: The book summarizes my recent research in biblical studies and early Christian theology. The basic thesis is that Christian Scripture has its center in Jesus Christ. I argue that this can be seen using three different “tools,” and that these tools also help shape the scriptural canon. These tools are: (1) the Rule of Faith, (2) the nomina sacra, and (3) numerical patterns pertaining to the alphabet (focussing on 22 and 24: the number of letters in the Hebrew and Hellenistic Greek alphabets) and the divine Name (focussing on 26: the numerical value of the Tetragrammaton, YHWH).

Nomina sacra here refer to a strictly delimited selection of sacred names demarcations present in the Bible manuscripts, such as the triune Greek contractions for God (ⲑ̅ⲥ̅), Jesus (ⲓ̅ⲥ̅) and Spirit (ⲡ̅ⲛ̅ⲁ̅). I note that the most important words that make up standard Rule of Faith formulations are the same words that constitute the key nomina sacra (“sacred names”), such as God the Father, the Son Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit. My conclusion is that Rule of Faith, as a creedal summary of the faith, and nomina sacra from early on attained overlapping interpretive functions. Arguably, the most popular combination of nomina sacra is the christological expression Jesus Christ. These two key nomina sacra (written as Greek contractions and supplied with an overbar as ⲓ̅ⲥ̅ ⲭ̅ⲥ̅), significantly appear as inclusios, or ring compositions, in a number of New Testament canonical sub-units as follows (Tyndale House Greek New Testament, unless indicated otherwise):

Jesus Christ (ⲓ̅ⲥ̅ ⲭ̅ⲥ̅) as the first and last verses of Galatians (1:1 and 6:18), Ephesians (1:1 and 6:24), 2 Peter (1:1 and 3:18), the four Gospels and Acts (Matt 1:1 and Acts 28:31), the seven Catholic Epistles (Jam 1:1 and Jude 25), and the Pauline Corpus (Rom 1:1 and Phlm 25, in Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus).

Jesus Christ here makes up the key framework for these respective textual sub-units, with implications for exegesis and canonical sub-unit divisions. On a related note, Peter’s confession “You are the Christ” in Matthew 16:16 makes up the middle paragraph of Matthew’s Gospel as per the ancient paragraph division of early New Testament manuscripts. In all the above New Testament examples, Jesus is made the textual center.

LP: What impact do you hope this book makes?

Bokedal: The present book is a new way of understanding the Bible canon and the canon formation process. I hope the book will prompt serious consideration of what seems to have happened when the Christian Bible was formed – namely that the shaping of canonical sub-units, and the New Testament canon as a whole, emerged not only as a text-external, but also as a text-internal process, in which the included texts were weaved together from within the writings themselves. In this connection, I am pleased to see my British colleague Crispin Fletcher-Louis’ endorsement of the book: “There is compelling evidence here and … [the] work deserves careful scrutiny by all who seek to understand early Christian theology and its scriptural practices.”