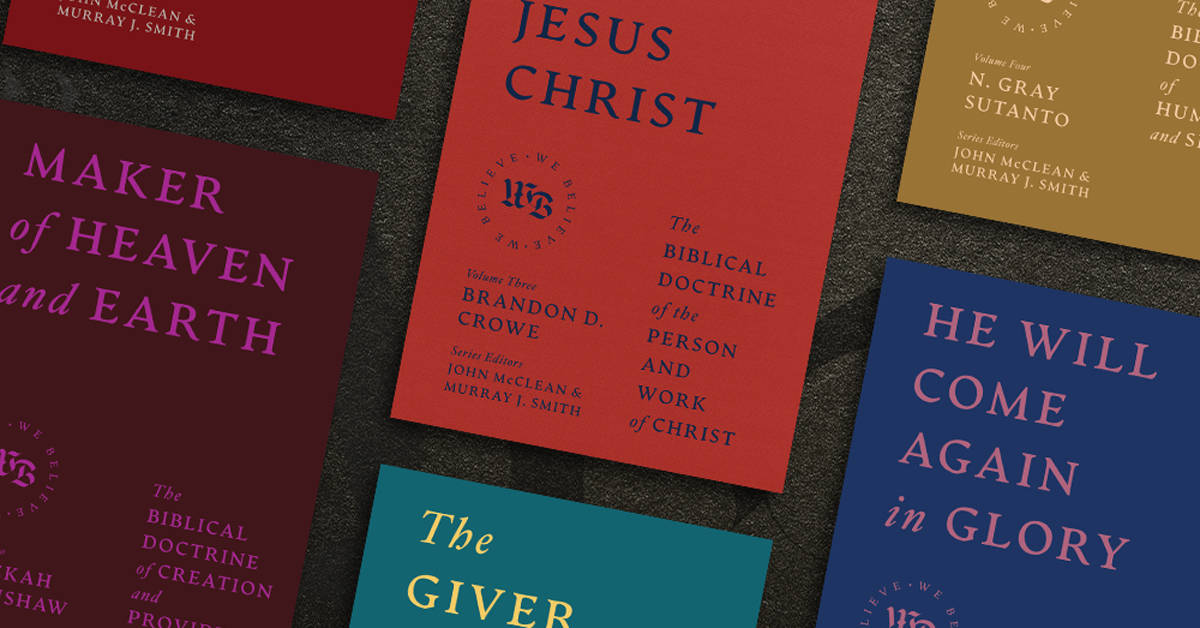

We Believe is a series of eight major studies of the Christian faith’s primary doctrines as confessed in the Nicene Creed and guided by the Reformed tradition. In each volume, trusted authors engage a major creedal doctrine in light of its biblical-theological foundations and historical development, drawing out its spiritual, ethical, and missional implications for the church today.

“Integrating biblical and systematic theology with a missional and pastoral passion, this series promises not only to inform but to transform readers through the riches of God’s word.” —Michael Horton

“Surely J. I. Packer is right to say regularly that the great need of our churches today is a renewal in catechesis. The “We Believe” series may well serve as a resource for that renewal by helping commend and clarify the faith and practice of the disciple of Jesus Christ.” —Michael Allen

The first volume in the series — The Lord Jesus Christ: The Biblical Doctrine of the Person and Work of Christ by Brandon D. Crowe — released this week. Here are the other seven forthcoming volumes in the series:

- One God Almighty: The Biblical Doctrine of the Triune God by D. Blair Smith

- Maker of Heaven and Earth: The Biblical Doctrine of Creation and Providence by Rebekah Earnshaw

- For Us and for Our Salvation: The Biblical Doctrine of Humanity and Sin by N. Gray Sutanto

- He Will Come Again in Glory: The Biblical Doctrine of the End by Murray J. Smith

- The Giver of Life: The Biblical Doctrine of the Holy Spirit and Salvation by J. V. Fesko (June 2024)

- He Spoke through the Prophets: The Biblical Doctrine of God’s Self-Revelation by John McClean

- One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church: The Biblical Doctrine of the Church by Guy P. Waters

An Invitation to Confessional Theology

We Believe is a series of eight studies of the primary doctrines of the Christian faith as confessed in the Nicene Creed and received in the Reformed tradition. The series marks the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea (ad 325) by re-affirming and advancing the Church’s confession. The title of our series is drawn from the first words of the Creed—the single Greek verb Πιστεύομεν—which introduces what has become the classic confession of the Christian Faith. Since the Church’s confession neither began at Nicaea, nor ended with its creed, We Believe examines the biblical foundations of the Church’s faith, traces its development (especially in the Reformed tradition), and applies its truths to the worship, life, and mission of the Church today. Since true theology begins in prayer and worship of the God who has revealed himself, each volume opens with a theme prayer, shaped by Scripture and the Church’s confession. Further, since even the deepest truths of the faith need to be simply expounded so they can be clearly grasped and faithfully lived, each volume closes with a series of theses, which summarize the doctrine covered in the book. We Believe provides a comprehensive and integrated biblical, theological, and missional treatment of the major doctrines of the Christian faith.

Biblical Revelation

The Church’s confession is rooted in and ruled by God’s revelation in Scripture. The Scriptures are “the Word of God written” and “the rule of faith and life” (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:2). The first part of each study, therefore, is devoted to a fresh examination of biblical revelation.

Fundamentally, our studies are tethered to the text of Scripture, and each volume in the series includes expositions of the primary biblical texts which form the doctrine under consideration. Moreover, since Scripture is the only “infallible rule” for its own interpretation (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:9), our studies seek to interpret Scripture by Scripture, initially by embracing the discipline of Biblical Theology. We begin—where God’s people have always begun—with the recognition that Scripture is God’s inspired and authoritative Word. We proceed by tracing God’s progressive revelation of himself and his purposes in the organically unfolding canon of Scripture, taking full account of its varied forms, while especially recognizing its fundamental, Christ-centered unity. This procedure is one we learn from Scripture itself. The Bible regularly claims that its revelation forms a single coherent narrative climaxing in the gospel of Christ, even as it also indicates that this narrative has many dimensions, and is revealed in a diversity of literary forms. Faithful Christian readings of Scripture—from Irenaeus and Augustine to Calvin and Kuyper—have, therefore, always recognized a fundamental unity within the rich diversity of Scripture—a unity which is conceptual (in that the Scriptures speak of the same God relating in consistent ways to the same created world), and narratival (in that the Scriptures narrate a single redemptive-history).

In the first part of each study, then, we look for the organic unfolding of God’s revelation from its seed form in the Garden of Eden (Gen 1–2) to its full flowering in the Garden-City of the New Jerusalem (Rev 21–22). As Augustine said, “in the Old Testament the New is concealed, in the New the Old is revealed.” So we read Genesis in the light of the Gospels, Exodus in the light of the Epistles, and Ruth in the light of Revelation. We follow the rich network of citations and allusions—the “inner biblical exegesis”—by which Scripture interprets Scripture. We outline the primary biblical themes relevant to each doctrine—God’s kingdom and covenant, God’s creation and blessing, God’s Son and people, God’s Spirit and temple—together with their many related sub-themes, as they inform and shape the Church’s confession. We use Scripture’s own words and categories to trace the drama of redemption from creation to new creation centered on Christ.

Following this approach, we recognize that the Bible fundamentally structures its own unfolding narrative, and organizes all its major themes, around God’s two primary covenants with Adam and Christ (Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:22). Reformed theology came to characterize these as the “covenant of works” and the “covenant of grace,” confessing that, from start to finish, God has related to his people and his world by way of covenant (Westminster Confession of Faith 7:1–6). Scripture thus presents each of the major post-fall biblical covenants—God’s covenants with Abraham, Israel, David, and the new covenant—as successive administrations of the single covenant of grace: the covenant which was first promised in the garden (Gen 3:15), climactically sealed by the blood of Christ (Matt 26:28 and Mark 14:24 with Exod 24:8), and which ultimately will be fulfilled in the new creation when the triune God comes to dwell with his people at last (Rev 21:3).

Above all—and consistent with the covenant theology we have just sketched—we take Jesus’s own word as our guide, and look for him, the Lord Jesus Christ, “in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27). Following Jesus and his apostles, we recognize that God “promised…the gospel…beforehand through his prophets in the Holy Scriptures” (Rom 1:3–4; cf. Luke 24:44–49; Gal 3:8; 1 Cor 15:3–5; 1 Pet 1:12). Christ himself—his person, his work, and his kingdom—is the climax and goal of the triune God’s gracious plan to redeem his people and his world. Indeed, Christ is the very “substance” of biblical revelation (Col 2:17; cf. John 5:39; Rom 10:4; 1 Cor 10:4; 2 Cor 1:20; 2 Tim 3:15; 1 Pet 1:10–12). The grace of God in Christ was not merely foreshadowed and prophesied in the Old Testament; it was mediated in advance to the saints of old, by the Spirit, through the “promises, prophecies, sacrifices…and other types” given to God’s people in that period (Westminster Confession of Faith 7:5–6). We therefore affirm that the Old Testament is both Christo-telic (in that it points forward to Christ as its goal), and Christo-centric (in that its types and promises really mediated God’s grace in Christ, through the Spirit). Thus, with John Calvin, we are right to “seek in the whole of Scripture…truly to know Jesus Christ, and the infinite riches that are comprised in him and are offered to us by him from God the Father.”

In thus seeking Christ in all the Scriptures, we find that later revelation in Scripture interprets earlier revelation in ways that are consistent with its original meaning; the later revelation shows the “true and full sense” (sensus plenior) in light of the fulfillment in Christ (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:9). The New Testament offers no radical reinterpretation, much less correction, of the Old, but unfolds the full meaning of God’s inspired Word. As B.B. Warfield put it, the Old Testament is like a room “richly furnished but dimly lighted,” such that “the introduction of light [from the New Testament] brings into it nothing which was not in it before,” but “brings out into clearer view much of what is in it but was only dimly or even not at all perceived before.” As we read the Scriptures as the unfolding narrative of God’s redemptive purpose, we learn to see, again and again, that Christ is the center and substance of the Scriptures, and so the center and substance of the Church’s faith.

Dogmatic Development

The Church confesses not only what is “expressly set down in Scripture” but what “by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture” (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:6). The second part of each study in the We Believe series, therefore, is devoted to an account of the dogmatic development of the doctrine under consideration. Far from being opposed to each other, Biblical Theology and Systematic and Confessional Dogmatics actually need each other; there is a necessarily reciprocal relationship between the two. While both disciplines deal with God’s special revelation in Scripture, they analyze it according to different principles.

The primary organizing principle for Biblical Theology is history—the organic unfolding of God’s work of redemption and his interpretation of the same in his inspired Word. The primary organizing principle of Dogmatics is logic—the rational organization of God’s revealed truth. As Geerhardus Vos observes, while Biblical Theology constructs a historical “line,” Christian Dogmatics constructs a logical “circle.” Thus, while Christian Dogmatics, including the Church’s creeds and confessions, generally follow the redemptive-historical shape of biblical revelation, they self-consciously set that redemptive history within the reality of the triune God and his relations to his world as these are revealed in all of Scripture. In the same way, while Christian Dogmatics fundamentally expresses itself using biblical language, it also employs extra-biblical language to summarize and synthesize biblical teaching, especially where Scripture uses a variety of expressions for the same reality, or where this is necessary to refute error. Since “the Word of God is living and active” (Heb 4:12), the God-given language of Scripture remains primary. Faithful Dogmatics rightly recognizes what John Webster calls the “rhetorical sufficiency” of Scripture. Indeed, since “the Old Testament in Hebrew … and the New Testament in Greek” were “immediately inspired by God,” the final court of appeal for all Christian Dogmatics is the words of Scripture in the original languages (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:8). Yet still, the same theological judgment can be expressed in a range of different conceptual and linguistic forms, and the faithful presentation and propagation of biblical truth sometimes requires extra-biblical expression.

There is, moreover, a real history of doctrinal development to be traced through the ages of church history. As the very Word of the living God, the Scriptures possess an inexhaustible depth. As the Church reads and re-reads God’s Word in an ever-changing world, we find that there is always more to confess regarding God and his ways in the world, and always more to celebrate in the depths of his “being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth” (Westminster Shorter Catechism 4). Herman Bavinck states it well:

“Scripture is not designed so that we should parrot it but that as free children of God we should think his thoughts after him…so much study and reflection on the subject is bound up with it that no person can do it alone. That takes centuries. To that end the church has been appointed and given the promise of the Spirit’s guidance into all truth.”

As each generation has read the Scriptures, confessed the faith, proclaimed the gospel, instructed children, discipled converts, and refuted errors, the Church—under the oversight of its living Lord, and by the enabling of his Holy Spirit—has deepened in its grasp of biblical truth. The Church has learned again and again that “the Lord hath yet more light and truth to break forth from His Word.” The foundational doctrines of God and Christ were fundamentally established in the Church’s early centuries, and codified in the ecumenical creeds, such that they received only incremental refinements thereafter. Other doctrines, however, no less crucial to the life of the Church—for example, the doctrines of Scripture and authority—received considerable development in the medieval, Reformation, and modern periods.

Doctrinal development, however—at least where it can be considered faithful—never moves beyond Scripture; it only ever penetrates more deeply into its truth. Faithful Dogmatics is thus not the imposition of a foreign grid onto Scripture, but a complementary means of interpreting Scripture by Scripture. In doing so, we make use of sanctified human reason. For while the Fall has corrupted the human mind (Rom 1:21–23; Eph 4:17–18), that same mind is renewed in Christ and by the Spirit (Rom 12:2; 1 Cor 2:10–13; Eph 4:23), and as such can play the role of servant in the task of theology. Thus Francis Turretin helpfully distinguishes between revelation as the “foundation of faith” and reason as the “instrument of faith,” which can serve to “illustrate” and “collate” biblical passages or arguments, to draw out “inferences,” and to help assess whether various positions agree or disagree with what has been revealed.

The Church has been at this task for nearly two-thousand years, and there is a great deal to be learned from the wisdom of the ages. For this reason, each volume in the We Believe series provides a survey of the historical development of the doctrine under consideration. In charting this development, we give the Church’s creeds and confessions pride of place. For while Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Turretin, and Bavinck—among a host of others—have provided significant insight into biblical truth, the Church’s creeds and confessions reflect the official teaching of the Church as Church or—perhaps better—the common teaching of the Church’s elders, that is, the teaching of those appointed by the Spirit, and charged with guarding and promoting the apostolic gospel and, indeed, “the whole counsel of God” (Acts 15:1–35; 16:4; 20:27–28; 1 Tim 3:2; 5:17–18; 2 Tim 2:2; Titus 1:9).

The Church’s teaching is always subordinate to Scripture. Scripture is the magisterial authority, the “rule that rules” (norma normans); the Church’s teaching is a ministerial authority, “the rule that is ruled” (norma normata). In the order of authority, “the Supreme Judge, by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, and all decrees of councils, opinions of ancient writers, doctrines of men, and private spirits, are to be examined, and in whose sentence we are to rest, can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture” (Westminster Confession of Faith 1:10). At the same time, in the order of knowing, there is wisdom in beginning with the Church’s confession. We rightly take the Church’s teaching as our guide in reading, interpreting, and applying Scripture. We learn the truth from our elders as they teach us the truth from God’s Word. This yields an iterative process: the Scriptures form our confession; our Scripturally-formed confession provides the lens through which we read the Scriptures, and; our further reading of the Scriptures further refines our confession.

We Believe stands unashamedly in the Reformed confessional tradition, and seeks to defend and advance it. There are, of course, significant differences between the various Christian confessions. While the whole Church receives the doctrine of the ecumenical creeds (the Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian creeds, together with the definition of Chalcedon), the later confessions present divergent views on a host of significant matters. It is our conviction that the Reformed confessions, especially the Three Forms of Unity and the Westminster Standards, present the best—that is, the most fully biblical—account of Christian truth. That very tradition, however, has always aimed to contend for “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) and has thus championed a kind of Reformed Catholicity. Our approach in the We Believe series is therefore eirenic, and ecumenical. We write from the perspective of the Reformed tradition, but for the Church catholic.

Moreover, while the Reformed confessions of the sixteenth century are a high point in the development of the Church’s doctrine, they are not the end point. The body of Christ will not “attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of stature of the fullness of Christ” (Eph 4:13), until Christ fully unites us to himself by his Spirit, when he raises his people from the dead, and perfects us by his glorious presence (1 Cor 15:42–49; Phil 3:20–21). The bride of Christ will not be fully purified, “without spot or wrinkle,” until the Lord returns and presents us to himself “in splendour” (Eph 5:27; Rev 21:2, 9). The city of God will not be complete until God himself comes to dwell among us in all his fullness and illumine us with his light (Rev 21:3, 22–23). A Reformed commitment to the creeds and confessions is, therefore, not an end point, but a stimulus to further biblical exposition and dogmatic clarification. As a work in Christian Dogmatics, We Believe does not merely aim to retrieve or to repristinate the Reformed tradition, but to constructively develop it, always under the authority of God’s Word. If this series makes a modest contribution to the Church’s pilgrimage to maturity in Christ, it will have achieved its goal.

Truth for Worship, Life, and Mission

The Church’s maturity in Christ involves far more than doctrinal faithfulness and clarity. The drama of redemption, which forms the Church’s doctrine, aims ultimately at discipleship and doxology. The third part of each study in the We Believe series, therefore, briefly considers the ways in which the doctrine under consideration shapes the Church’s worship, life, and mission. While the discussion here is necessarily indicative rather than exhaustive, we aim to demonstrate how biblical doctrine creates a moral vision for all of life. This includes, at the broadest level, observing the way in which the particular doctrine provides the basis for biblical principles for Christian worship, life, and mission, whether these are given explicitly in the biblical text (e.g. Matt 7:12 the “golden rule”), or summarized from biblical revelation as a whole (e.g. “the sanctity of life”). It includes, more sharply, consideration of the way in which Christian doctrine grounds the moral law, summarized in the Ten Commandments, and further summarized in the two great commandments of love for God and neighbor (Westminster Confession of Faith 19.2, 5; see esp. Exod 20:1–17; Deut 5:6–21; Matt 22:37–40; Rom 13:8; Gal 5:14; Jas 2:8). It also includes, further, consideration of the wealth of biblical examples which illustrate—both positively and negatively—the wisdom of life according to God’s law. Crucially, since Reformed theology has always emphasized the necessity of the work of the Spirit in enabling faith and renewing those who were lost in sin by uniting them to Christ, this section also considers the way in which each doctrine highlights the gracious work of God in enabling his people “to live and work for his praise and glory” (A Prayer Book for Australia).

Almighty God, you are enthroned on the praises of Israel,

and all nations will worship and glorify your name.

Grant us counsel, instruct us, and reveal yourself to us,

that we would enjoy and glorify you in heart, soul,

and mind in this life and forever.

Through Jesus Christ our Lord,

who lives and reigns with you

and the Holy Spirit, one God,

now and forever.

Amen.

John McClean, Vice Principal and Lecturer in Systematic Theology and Ethics, Christ College, Sydney

Murray J. Smith, Lecturer in Biblical Theology and Exegesis, Christ College, Sydney

This post was adapted from the We Believe series introduction by John McClean and Murray J. Smith.