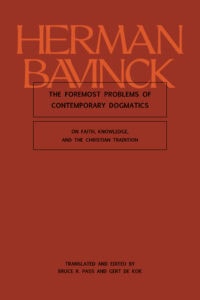

Bruce Pass and Gert de Kok are the editors and translators of The Foremost Problems of Contemporary Dogmatics: On Faith, Knowledge, and the Christian Tradition, written by Herman Bavinck and just recently translated into English for the first time. A series of lectures delivered at the Free University in 1902, this book provides a unique window into Bavinck’s thought, as he speaks candidly about the limitations and failures of Reformed theology and the relative merits of modern thinkers.

In this interview with Pass and de Kok, we discuss the long road to bringing these lectures to light.

Bruce R. Pass is honorary senior research fellow in the School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry at the University of Queensland, Australia. He is the author of The Heart of Dogmatics: Christology and Christocentrism in Herman Bavinck and editor and translator of On Theology: Herman Bavinck’s Academic Orations.

Gert de Kok is pastor at the Dutch Reformed church of Nunspeet and Hulshorst, Netherlands.

Lexham Press: Thank you for this collaborative interview. Tell us the story behind The Foremost Problems of Contemporary Dogmatics: On Faith, Knowledge, and the Christian Tradition and describe its basic thesis.

Bruce Pass & Gert de Kok: This book has an interesting story. For more than a hundred years the manuscript has reposed in the Bavinck Archive, which is currently housed at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. In 2018, I took photographs of the manuscript and Gert and I began the slow and painstaking work of transcribing and translating. Thankfully, it is quite polished, prosed with copious footnotes that are (mostly) accurate and not too difficult to identify. The book itself is a series of lectures Bavinck delivered at the Vrije Universiteit at various times across the twenty years he taught at that institution. He wanted to present his students with a very detailed account of what he perceived to be the biggest problem confronting Protestant theologians at the dawn of the twentieth century. Interestingly, Bavinck thought the foremost problem was not the incarnation or atonement or any other head of doctrine. This is surprising, because he was living in an age when Protestant theology had for some time been taking the traditional accounts of these doctrines in very ‘untraditional’ directions. Bavinck, of course, disagreed with much of this. But he thought the foremost theological problem was the act of faith. How faith is conceptualized affects everything.

LP: What contribution do you hope to make with your book?

Pass & de Kok: Naturally, we think this book is remarkable. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t have spent 6 years bringing it into English! It is remarkable in a number of ways.

First, for those interested in Bavinck, this is an important text that sheds light on Bavinck’s reception of his own theological tradition. Additionally, there are hundreds of pages where Bavinck shows us what he thinks of the development of philosophy of religion in the nineteenth century. These lectures need to be read alongside the summarized accounts of the same topics in the first and fourth volumes of Reformed Dogmatics. The basic conclusions are the same but there is a lot of detail in The Foremost Problems that you don’t have in Reformed Dogmatics. The Foremost Problems is also arranged differently. The lectures form an intellectual history of the act of faith and its conceptualization. This allows Bavinck to say more on this topic and develop his thoughts in a more sustained manner. if he did this for every topic in Reformed Dogmatics, it would have been forty volumes rather than four.

Second, Bavinck’s conclusions provide an interesting counterpoint to those of Karl Barth. Barth wrote his own version of these lectures. Credo is his account of the foremost problems of contemporary dogmatics, and Barth presents an intellectual history of the nineteenth century in Protestant Theology in the Nineteenth Century. Although these two thinkers come up with quite different answers, their theological intuitions are much closer than one would think. It pays dividends to sift through their differing positions. On the one hand, Barth challenges Bavinck and problematizes his central argument. On the other, Bavinck exposes the weaknesses of Barth’s own solutions. It is very instructive to read these thinkers side by side.

Third, this book is just provocative. It makes you think. For better or for worse, Bavinck has a very psychological approach to the theological task. He thinks that we need to get faith ‘right’ so that we don’t jeopardize the fundamental doctrines of Christianity. Here, it is interesting to observe the intersection of Bavinck’s argument with the intellectual history presented by Carl Trueman in his recent book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. Trueman shows that the psychological turn that Bavinck identifies is still controlling the theological/ethical conversation in the twenty-first century. Whether or not this psychological turn is the foremost problem, Bavinck certainly gets you thinking about where the solution might lie.

LP: Can you describe a particularly surprising or enjoyable aspect that you discovered from writing your book?

Pass & de Kok: It has been a great project in teamwork. Working on it together has meant that we could challenge each other to be consistent and precise ALL the time. It is an immense challenge to focus on the million details and still zoom out to the whole. An archival project like this one has additional problems. The sleuthing requires immense patience and creativity too. Our partnership, however, consistently enhanced and strengthened our individual efforts. We have learned a lot about Bavinck and nineteenth-century theology in the process. This in itself is reward for our efforts, but we’re mainly delighted to make this source available for others.

LP: Please, share with your readers something surprising about yourself that only your friends would know?

Pass: Before I studied theology, I studied piano at the Hochschule fuer Musik ‘Franz Liszt’ in Weimar. It was a terrific place to study and a remarkable experience to live in a city with connections to so many literary and musical figures. But this has also helped me appreciate the broader cultural framework of Protestant thought in the nineteenth century that forms the focus of Bavinck’s lectures. Being familiar with the artistic life that ran with the intellectual currents of any given era helps you understand its texts in a different way. When I am teaching philosophy or theology, I try to help students make these connections too. I might play them a short video of a relevant musical example. Nothing explains “Nietzsche” more clearly than the prelude to Act 3 of Wagner’s Siegfried. Or if you want to understand the origins of Kulturprotestantismus, have a listen to Mendelssohn’s Reformation symphony.

de Kok: In 2012 I started my BA theology in Groningen. The choice for Groningen was merely practical — I already studied economics there. Born and raised a real ‘gereformeerde’ believer, the more logical choice would have been to go to the Reformed University of Apeldoorn — both my parents in their day finished their theology degrees there! However, to my pleasant surprise, it was in Groningen that I encountered Herman Bavinck. Through my work as a student-assistent to professor Henk van den Belt I was given the opportunity to do an abundance of close-reading of his texts. Bavinck helped me to realize that you do not need to be afraid of challenges posed by the academic world. Bavinck was deeply rooted in faith and open to explore the world, since “every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights …” (James 1:17).