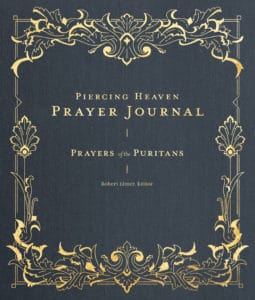

In this excerpt from the foreword to the Piercing Heaven Prayer Journal, Jenny-Lyn de Klerk illuminates the Puritan practice of prayer and journaling for modern readers.

For centuries, believers have turned to the Puritans as guides for Christian living because they were experts. Combining their deep knowledge of Scripture and equally deep knowledge of human nature, they developed a rich understanding of what it means to be in relationship with God. And though, according to the Puritans, spiritual disciplines like praying and journaling made up a life lived with God, the practices themselves were not the point. Rather, such practices were used to craft, with God’s help, a whole-self, whole-life devotion to God—that is to say, a devotion that included every part of one’s being and every aspect of one’s existence. This devotion was not just a means of offering oneself to God but also of receiving his love and thus being close to him as a friend.

One of the reasons the Puritans placed such a strong emphasis on this holistic devotion was because of the weaknesses they perceived in the national church of their time. Though some were ministers in the Church of England themselves, they eventually had to draw a line beyond which they were not willing to go—and on the other side of that line was the Book of Common Prayer. However, the Puritans were not against this prayerbook itself. Rather, they were against the national church’s prescription for ministers to only use its prescribed forms for public prayer to the neglect of “free prayer” or “prayer in the Spirit”—that is, prayer that relies on the Spirit’s help. The Puritans believed that Christians should rely on the Spirit’s help because enabling such prayer is part of the Spirit’s role as the Third Person of the Godhead, according to passages like Romans 8:26.

This is a perfect example of the Puritans’ emphasis on holistic devotion empowered by God himself. And it is perhaps explained best by the preeminent Puritan theologian John Owen. In his Pneumatologia, Owen taught that the Spirit helps us in prayer by (1) showing us our own wants and how God supplies our wants in the promises of the gospel, (2) enabling us to see Christ’s beauty in these promises and to place our faith in him, and (3) inspiring in us love of and delight in God and godliness over love of and delight in ourselves and our own comfort. This kind of prayer is both sensitive to our unique needs—as the Spirit helps us to analyze our current situations, have suitable feelings and use suitable words for what we are currently going through, and pray effectively for others in our lives according to our personal relationship with them—while never losing sight of the greatness of God, his word, and his glory. Thus, Owen explained that prayer is not something utterly above us or without relevance to our specific life situations but is communicating with God using all we are, exactly where we are.

Based on this theological framework, the Puritans reasoned that though it is fine to use prayers written by other people to aid your own prayers, you must do so with a full heart and mind and must never replace the Spirit’s aid in prayer. This is because a good prayer is not just saying the right things or even saying them with the right attitude or in the right position or with the right tone of voice—it is communing with God himself.

Perhaps you have experienced this before. You probably know what I mean when I say that sometimes in prayer, you are led to articulate everything you have been thinking about in a way that suddenly makes sense in light of Scripture. And in that moment, you feel God’s presence with you and are reminded that he hears you, loves you, and is providentially working in even the intricate details of your life, your family, and your church, so that you leave your prayer time with a sense of deep peace about your fate and that of your friends, family, and even the universe. Jesus is paying attention, and being able to pour out your heart to this Friend of all friends shapes you, changes you, and makes you a Christian.

Such prayer in the Spirit provides a great snapshot of what Puritan spirituality was all about, and this journaling edition of Puritan prayers offers the best way for us to use their prayers and helps us think Puritan-ly about devoting our own lives to God.

In fact, journaling is another spiritual discipline that we can learn about from the Puritans. In the seventeenth century, many kept notebooks (called “commonplace books”) in which they jotted down random but meaningful pieces of information. Christians often used them to keep track of Bible verses, notes from sermons, explanations of doctrines, and reflections about their lives. For example, in her notebook, the Puritan author Lucy Hutchinson wrote down two personal statements of faith, important points from Calvin’s Institutes, a list of arguments that prove God’s existence, and a poem about the love of God. Such immediacy and diversity show us that on a regular, everyday basis (even in the most difficult times of her life, like after her husband’s death), she was devoting her life to God—he consumed her thoughts, filled her time, and took up space in her physical possessions.

Similarly, the Puritan philanthropist Mary Rich, Countess of Warwick, kept a daily diary in which she recorded her experiences in meditation, which were inspired by what she read in the Bible and good books as well as what she observed in nature. Such meditation influenced not only her own life but also the lives of others, as it solidified her commitment to share her knowledge of the faith with her fellow Christians; exhibit patience with her invalid husband, who struggled with anger; and give generously to the poor. Her journal entries were encouraging not only in the moment when she recorded the meditations but also in later months, when she reread her diary to remember how faithful God had been in her life.

Such energetic Christian living is also seen in a theological treatise that Hutchinson wrote for her newlywed daughter, wherein she included Bible verse citations in the margins as a means of encouraging Barbara to engage with the physical book and meaning of the text herself. As you can see, Puritan spirituality was a reading, writing, thinking, praying, moving, journaling kind of spirituality that engaged the whole person in their whole life, through the amazing, the ordinary, and even the messy.

So, as you read and journal in this volume, you might, like Hutchinson, write down ideas that come to mind, or like Rich, record how these prayers inspire you to help others. Or perhaps you might look up relevant Bible verses like Hutchinson did, or ask for the Spirit’s help and closeness as you seek to draw near to him, interpret your life, disciple others, and bask in the beauty of Christ’s fulfillment of gospel promises like Owen. Regardless of what you write or say or pray, may these Puritan prayers fill your soul with dreams of Jesus and heaven, leading you to the kind of devotion that relishes in giving love and receiving it, which is so satisfying that it reminds you why and how you’re a Christian in the first place.

This post is adapted from the foreword to the Piercing Heaven Prayer Journal edited by Robert Elmer (Lexham Press, 2022).