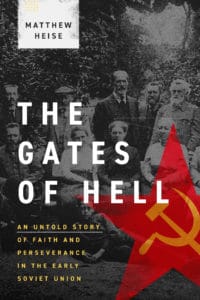

In this excerpt from The Gates of Hell, Matthew Heise traces the world shaking events surrounding the end of World War I and their effect on the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia.

JUNE 1918—An idyllic summer day in the Crimea, with trees blossoming and groaning from the fruit peculiar to that bountiful region near the Black Sea. Cherries, strawberries, plums, and mulberries blanketed the countryside. In the old German village of Neusatz it was a memorable day: the Hörschelmann family was marking the ordination of Friedel Hörschelmann, the eldest son of Pastor Ferdinand Hörschelmann Sr.

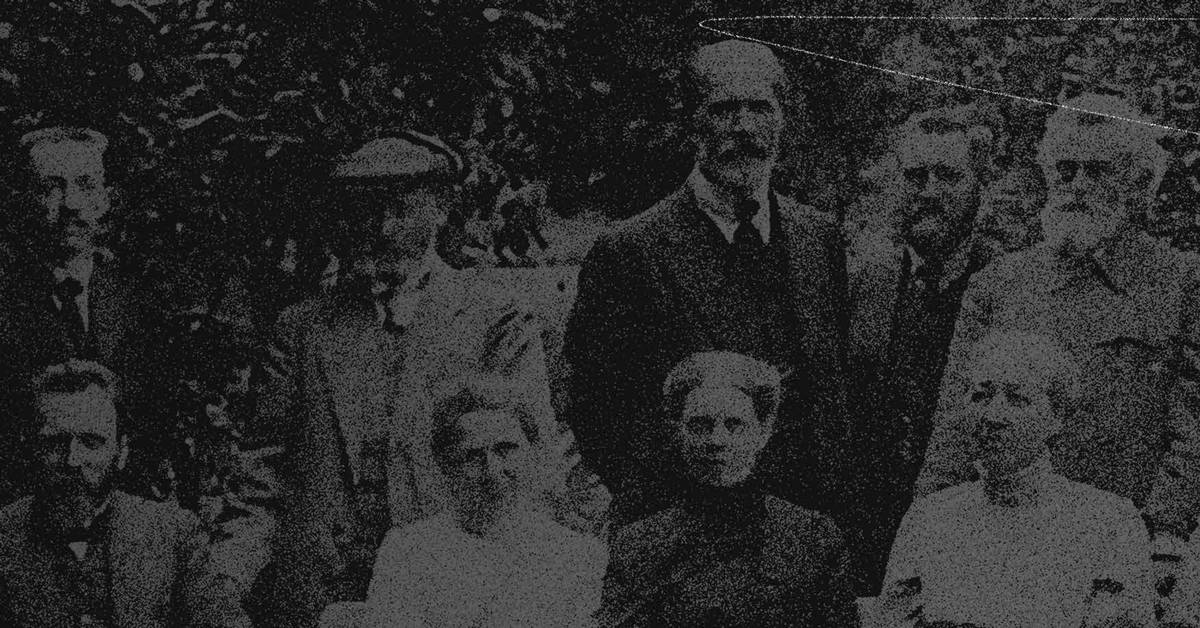

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia and all Christian churches had recently experienced severe tribulation due to the Bolshevik Revolution of the previous fall, a revolution that promised a robust battle against what it considered outdated religious dogma. The Bolsheviks hadn’t wasted time after taking power, crafting a law in January 1918 separating the church from the state and the school from church. Despite these forbidding signs, though, the church was far from dead. On this day, pastors from the surrounding region joyfully gathered along with their families to celebrate Friedel’s ordination. They commemorated the occasion with a photo, which now appears on the cover of The Gates of Hell and can be seen below.

Despite the recent turmoil throughout the country, the fact that such a serene setting still existed in Russia must have comforted believers. But within twelve years of this gathering, both elder and younger Hörschelmanns would die in Soviet Gulag labor camps. Three of the other pastors in the photo, Arnold Frischfeld, Arthur Hanson, and Emil Choldetsky, would also walk the path to Golgotha that so many believers in Russia would travel. The young man lying in the foreground, a future organist for Sts. Peter and Paul Lutheran Church in Moscow, was the youngest son of Ferdinand Hörschelmann. He would also serve a stint in the Gulag and eventually be murdered when he was thrown from a train by Soviet criminals.

But on this day, all those tragedies lay in the future. The Lutheran Church was seeking to find some solid ground in the world’s first officially atheist nation.

A World in Flux

Lutherans worldwide had been eagerly anticipating the year 1917. Celebrations marking the four hundredth anniversary of the Reformation had been in the planning stages for several years, and now, despite the cataclysm of a world war, they would be observed with fervor. One of the American planning committees had been formed as early as 1914 and had united representatives of the General Council, the General Synod, and the United Synod South. Another committee, the Reformation Quadricentenary Committee, was led by two Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod pastors, Otto Pannkoke and William Schoenfeld.1 The Missouri Synod was in the process of commissioning a new translation of the Book of Concord that would ultimately be released in 1921.2 The Missouri Synod’s publishing arm, Concordia Publishing House, also printed a book on the Reformation in all its aspects, edited by William H. T. Dau and entitled Four Hundred Years. An ocean away, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia was similarly compiling a set of articles into a book edited by Theophil Meier entitled Luther’s Heritage in Russia. The book chronicled the almost 350-year history of the Lutheran Church in Russia, the authors solemnly reflecting not only on the joys but also the persecutions of the past.

In St. Petersburg, the heart of the Lutheran Church in Russia, many events were scheduled to celebrate. At St. Peter’s, the largest church in the center of the city, three evenings were planned. On the first, Rev. Wilhelm Kentmann presented on the basics of the Augsburg Confession, and during the following two evenings he read Luther’s work on “The Freedom of the Christian.” These were followed on Reformation Day by a morning service led by Pastors Kentmann, Paul Willigerode, and Karl Walter. There was also a celebration for the youth of St. Peter’s Lutheran School (called the Peterschule), with Principal Erich Kleinenberg and his assistant, Alexander Wolfius, presenting, and the girls’ choir performing. The day ended with a church packed full of all the German-speaking Lutheran congregations in St. Petersburg robustly singing the hymns of the Reformation.

In Moscow, a fifteen-minute walk from the Kremlin at Sts. Peter and Paul Lutheran Church, Rev. Meier spoke of the dangers threatening Lutherans in Russia: “But has not much of our sacred heritage been born in the sounds of the Reformation? Thanks be to God, the echo of revolution is silenced in our hearts by the echo of the Reformation!” The congregation followed Meier’s stirring words with the singing of “A Mighty Fortress.” Those words of Meier would sound a theme repeated by others in the coming years: the spiritual theology and musical strains of the Reformation versus the worldly politics and atheistic anthems of the Bolshevik Revolution.

The tragic events taking place on the battlefields of Europe that Reformation Day in 1917 would soon result in a peace that would allow the Lutheran churches of Russia and America to establish more intimate contacts. The Lutherans of both nations had much in common. Questions about the loyalty of ethnic Germans in Russia and America led to suspicion among those considered more “native.” Due to the very language they used in their worship services, both groups were accused of being sympathetic to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s imperialistic ambitions.

But now that the “war to end all wars” had exacted destruction on an unprecedented scale, the interest of American Lutherans was drawn to the shattered lives of their brothers and sisters beyond their borders. The fact that many immigrants from the Volga region had resettled in the American Midwest virtually compelled Lutherans to take an interest. They retained contact with their families overseas and would act on the consciences of their fellow Lutherans in America in the future. So as a result of the war, American and Russian-German Lutherans began a partnership that would only take on added meaning as the Bolshevik Revolution began its assault on religion and the Lutheran Church in Russia later that year. American Lutherans would come to appreciate the deeper meaning behind the biblical phrase, “my brother’s keeper,” and a remarkable man would soon step to the forefront and keep the plight of Russia’s Lutherans foremost in their minds for many years to come.

This post was adapted from The Gates of Hell: An Untold Story of Faith and Perseverance in the Early Soviet Union by Matthew Heise (Lexham Press, 2022).