Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, has died. It is perhaps odd that I, a self-identified evangelical Protestant with sons named after Reformers (Calvin, Latimer, and Cranmer), should find myself both grieving the passing and grateful for the witness of such a public intellectual believer. But I do.

Two Degrees of Separation

But as for you, continue in what you have learned and have firmly believed, knowing from whom you learned it. (2 Tim 3:14)

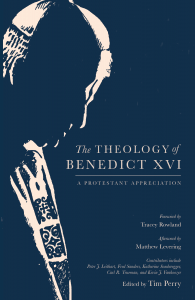

For me, the connection is deeply personal in two ways. It is personal, first of all because it was the late Holy Father who brought me back into writing after several years away. Two former students, Jesse Myers and Joey Royal, conspired around 2017 to compel me to edit a collection of essays from evangelical theologians across the spectrum of the movement (Baptists, Wesleyans, Presbyterians and Episcopalians all contributed) offering appreciation for and insight into the major theological themes of Ratzinger’s work. Jesse and Joey had to work to persuade me, but my agreement ultimately hinged on the opportunity to reflect more on a man who had walked with me since I was assigned the reading of The Spirit of the Liturgy as part of my preparation for ordination in 2010.

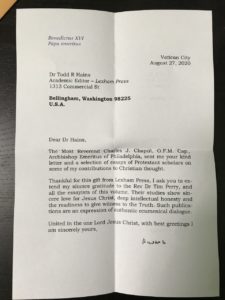

It is personal, second, because Benedict actually read the book and wrote the press to thank us for it. In the Providence of God, one of the contributors (indeed, perhaps the most Protestant of all of us) passed the book along to a retired Archbishop, who in turn sent it to the Vatican. Several weeks later, the press received a letter of thanks from a humble man who seemed genuinely surprised and grateful that a group of “separated brothers and sisters” would want to interact with his thought, and that they would do so with care, criticism, and respect. He who just happened to be the 264th successor to St. Peter called the collection an exercise of true ecumenism.

I was once advised that any who would aspire to be a good theologian should apprentice himself to a recognized theologian for a lifetime, reading everything that theologian ever wrote. My colleague didn’t just think the theologian should be well known but that they should be good. What he meant by “good” was one who combined both intellectual brilliance and holiness of life. When I told him that I had already apprenticed myself to Ratzinger, he replied, “Me, too.”

The Word

Remember your word to your servant, in which you have made me hope. (Psalm 119:49)

So, what have I learned? I hardly know where to begin. I could talk about the deep integration of reason and revelation. I might mention reverence for God in the act of worship. The primacy of the fathers as guides in biblical interpretation. Even the possibility of a deep yet modest Marian devotion compatible with the Protestant confessions. On friendship with Jesus and the life of prayer, he is a master. Ratzinger enriched my understanding of all of these. Oddly enough however, today I find myself returning to the subject of Holy Scripture. Ratzinger taught me how to be a Bible Christian, again.

He taught me, first, that the Bible was one book. Leave aside for a moment the Reformation debates about the size and scope of the canon and about the complicated relationship between Scripture and tradition (whether “T” or “t”). Ratzinger was a man of one book—the Bible—and for him that book was one. That meant he read and exposited the Bible as one would a “loosely structured historical novel” (the phrase is Hans Frei’s), expecting that what was unclear in earlier passages would be deepened and clarified by later ones. What was in the Old concealed was in the New revealed; what was in the New revealed was amplified by a thorough reading of the Old. The first part of his lectures on Mary, Daughter Zion, are thus anchored firmly in the Old Testament, patiently unfolding insights that are far from fanciful isegetical leaps of imagination, but are the fruit of years of slow, careful and prayerful reading. When he reads in this way, he models his own great teachers, St. Bonaventure and St. Augustine. When I relearned to read this way, I learned to read the Bible the way my grandmother did (as Orange a Protestant as ever there was). A way that had been rigorously trained out of me (I’m sure unwittingly) by Bible College and Seminary biblical studies.

Not only was the Bible one book, but, second, it had one author: God. Of course, that did not mean the eschewing of biblical studies—as his own trilogy on the life of Jesus makes obvious. Rather, it meant that biblical studies (at least for the believer) had a real and finally limited purpose. After all the form, source, redaction, and sociocultural work was done—and it had to be done—one had merely started biblical study. Now it was time to read again with a second naivete and prayerful attention, asking what God, the single author who unified the disparate voices of all the human authors, redactors, editors, and compilers, into One Voice intended to say. The Bible, Ratzinger taught me, was and is taken up into the saving work of God, and as such truly was His Word given in His words.

God’s Word given in human words which are at the same time God’s words given to God’s people. That’s the third facet of Ratzinger’s teaching on Holy Scripture. One book by One Author for One people: the Church. This may seem obvious, but the implications have been huge, especially for my preaching. I had been taught that Bible preaching involved setting the contents of the Bible in their proper contexts, and seeking to discern some sort of universal truth or principle that could then be translated into the context of my hearers. Think, Five Steps to a Happy Household from Proverbs. But to preach in this way was to assume the Church had an existence prior to the Word, and to which the Word could be attached (or not) as needed. But Ratzinger taught me (as indeed Luther would have, had I paid attention) that the Church was created by the Word and continually found herself (yes, she is feminine) in, with and under that Word. And that meant my task as a preacher was not to bring principles from the Word to my people, but instead to bring my people from their worldliness to the Word, there to find judgment and grace, law and Gospel. To open the text, and let the Word absorb the World (the phrase is George Lindbeck’s).

A Final Prayer

Let your priests be clothed with righteousness, and let your saints shout for joy. (Psalm 132:9)

So today, I find myself sad, both for myself and for the world, at the loss of yet another public Christian whose witness, while not perfect, certainly was faithful. And I find myself thankful for having been given a mentor who quietly and humbly taught so many even as he taught me. I do not know whether, in God’s Providence, Benedict XVI will be recognized as a Saint one day. I do know—I know it in my bones—that the Church Triumphant has gained a new member and that the Church Militant has, as a result, an even more powerful intercessor than he was only yesterday.

O God, in whose presence the dead are alive,

and in whom your Saints rejoice full of happiness,

grant our supplication that your servant, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI,

for whom the fleeting light of this world shines no more,

may enjoy the comfort of your light for all eternity;

through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

AMEN.

This guest post was written by Tim Perry, editor of The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation (Lexham Press, 2019).

To celebrate Benedict XVI’s life and theological legacy, this collection of essays is on sale through the end of this month.